The Childhood I Wish I Had

As Simon and I prepare to grow our family this year, I’m poring over parenting books, something I’ve always been excited to do. One book that caught my eye during my visit to the local library was Esther Wojcicki’s How to Raise Successful People. As a girl working in Silicon Valley who’s always admired the ultra-successful Wojcicki sisters, I was curious to hear what their mother (hailed as the “The Godmother of Silicon Valley”) had to say about parenting.

The first chapter of the book told the story of Woj’s childhood, from her own perspective. She says that to become better parents, you need to have done the work to be your own therapist and make sense of your childhood experiences. Even though I’m sure in certain instances we’ll naturally resort to parenting the way we were parented, Simon and I have found ourselves saying to each other “I don’t want to become my mom.” But what exactly does that mean? Let’s rewind.

My childhood

My parents were only in their 20s when they had two kids while immigrating to the U.S. with little English and no money. We grew up with no other family around and they raised us with little outside help. But seeing my parents struggle to make it in America taught me the immigrant mentality of resourcefulness and determination.

We were poor, extremely frugal, and never ate out or traveled much outside California. We definitely didn’t play video games or get the newest toys. I was a latchkey kid, and even spent a summer at a Boy and Girls Club, which I didn’t even know was a charity until recently. I had little to no spending money, which was difficult for a girl who liked clothes and dress-up. I’d sometimes forfeit my lunch money just to save up. I sold candy to my classmates, collecting valuable quarters that contributed to my fun fund. Over the course of my childhood, my parents grew out of food stamps and were able to afford piano lessons and eventually send both kids to college. I still worked throughout college to make spending money and even pay some rent. Through poverty, I’ve learned that the silver lining is grit. I’m glad I had a childhood where I had to learn to cherish what we had and make up my own world to fill in the gaps. The best gift my parents could have given me was a humble beginning.

My mom was the youngest sibling herself. From my grandpa, she learned dedication and developed a strong work ethic. To this day, she is a extremely dedicated mom and wife. She is the operations behind the entire family. She’s the reason the laundry gets done, meals are home-cooked and healthy, the garden is watered, the trash taken out, the dentist appointments booked, the bills paid. She always made time to parent us, no matter what was happening in life.

However, as a child I never saw my mom “relax”; there was always a never-ending amount of things to do. Outside the home, the one thing my mom knew she excelled at was school and studying. That’s why she has multiple degrees and licenses for a range of professions. She valued education above all.

My dad is the older sibling. He came from true poverty, but that gave him an incredible amount of hustle. He grew up the class clown, the talkative popular class president who never studied for his tests but aced them. He’s brilliant. As a dad, he cracked jokes (though not always the best ones) and had a sharp wit that I somehow inherited, for better or for worse. He sang around the house, and danced with us. He has an endless sea of hobbies, and finds everything interesting. In college, he took photos, played guitar, basketball, volleyball. In his early working years, he traveled around the world and picked up tidbits of cultures that he’d teach us about. He taught us to butter our dinner rolls like the Europeans, pick up the phone with a “moshi moshi”, and got me practicing rolling my R’s at a young age.

As a natural hustler, my dad tried to DIY everything. He rearranged furniture all the time and devised plans to hack together budget-friendly “improvements” to the house. At 13 years old, I’d be the one helping him with construction and yard work. He also loved tinkering with toys and projects of his own — building contraptions for the garden, trying to recreate every tasty dish he’s ever had at a restaurant, turning old blankets into sleeping bags at the sewing machine. Many of the toys he bought from himself actually became hobbies I picked up: the DSLR camera kickstarted my passion for photography, and the guitar because my music instrument of choice, and the pirated copy of Photoshop that jumpstarted my interest in digital media arts and eventually, my career today.

Within the family, my dad was the decision-maker while my mom generally agreed. They were always united in their decisions and expectations for my sister and me. There was never good cop, bad cop. (Just bad cop and a guilty suspect — me!) Their rare arguments revolved around parenting. I remember when my dad argued that my piano classes were a waste of money but my mom thought education took precedent over savings.

I was the older sibling, so I had responsibilities and was expected to help out early on. I babysat my sister and the children of family friends, always leading a pack of kids around. As a kid myself, I knew how to invent games and engage other kids, keeping them safe and happy. At home, certain chores were assigned to me at an early age. For example, dishes were officially mine to do every night. I quickly understood that living in a household meant sharing responsibilities. You couldn’t indulge or have fun until the necessary work got done.

In high school, my dynamic with my parents changed as their primary focus shifted to getting me to a good college. On top of a grueling magnet school workload, I felt like I lived in confinement from anything fun because my 100% focus outside schoolwork was to be reserved for SAT studying. Because the vocabulary section of the test was my weakness (no doubt any ESL kid would relate), for a year my dad didn’t speak to me outside the “did you memorize your vocabulary words yet today?” My parents subscribed to the all-too-common Asian immigrant parent obsession that going to a good college and subsequently getting a high-paying job equated to ultimate life success. Everything else — happiness, purpose, fulfillment — was second priority.

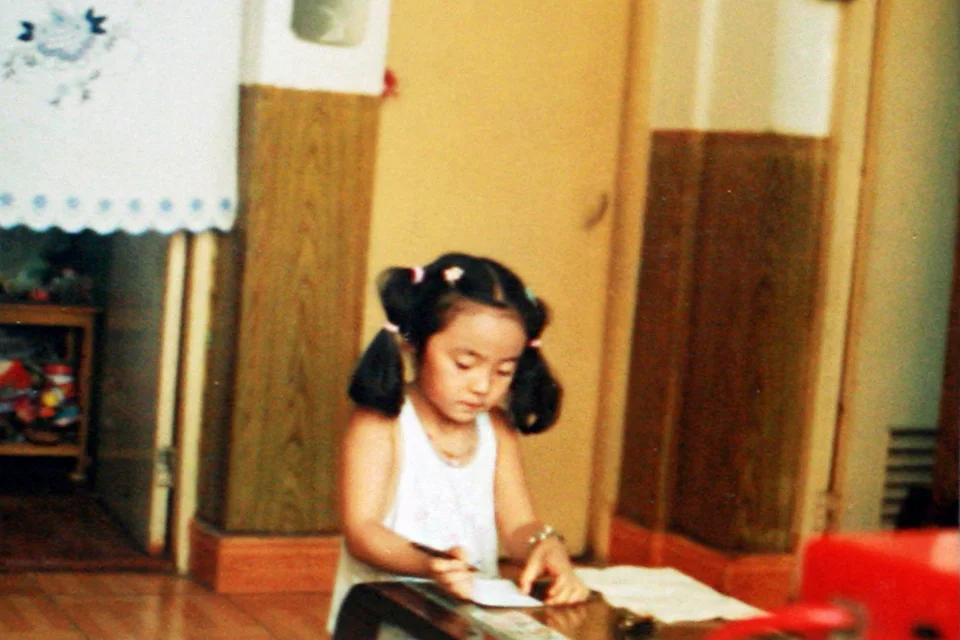

Mom and me, shortly after I moved to the U.S.

Our girl dad.

Things I think my parents got right

Fostered a sense of independence by letting me do things by myself: discover hobbies, be bored, make up games, dress myself, figure out breakfast, do my own school projects entirely (case in point — my 4th grade California Mission Project was heinous.) I walked to school at a young age and bought my own lunches with allotted spending money. They pushed us to get jobs and internships as teenagers, and when I turned 18, they expected me to move out for good. When they bought me my first (very used) car, my dad made sure I knew how to change tires and jump start the car. I never needed someone else to take care of my business, no boys, no TaskRabbits, no one but myself. I became a DIY-er. Reflecting back, this set them apart from most traditional Asian parents I know. They rarely checked up on me, and never ever coddled me. This fostered independence, which allowed me to imagine and play, ultimately developing an innate creativity and a love of lifelong learning for things I’m genuinely interested in. It also gave me the confidence and courage to take on anything I wanted.

Let me find things out the hard way. My parents always encouraged us to find our own answers, even if it meant failing in order to learn something. They held their tongues as they watched us make mistakes. We fed stray cats, crawled under barbed wire fences, ate all the candy we could get our hands on, and spent hours at the park every week without direct supervision. We rode bikes down steep hills without protection. They let me pick out a ridiculous shade of blue to paint my bedroom, which still haunts me every time I visit nowadays. Later in life, my dad encouraged me to follow my photography career dreams in New York after graduation, even though he kind of knew I’d return. (It was clear; he never sold my car.)

They never babied me. I was the rebel in the family, and I owned up to it. They never said superficial things just to make me feel better. They showed me that the world was full of hardship, but I could overcome it. They didn’t try to be our friends. They had their adult things, and they expected me to act like one.

Rewards or indulgences had to be earned. A visit to the mall or a McDonald’s dinner had to come as the result of some achievement. When we did well on an exam, my mom would ask how we wanted to be rewarded. These treats were rare, but instilled in us an important feedback loop that emphasized good things required work. She has since admitted to being more sparing and frugal that was necessary at the time, but it taught us the right lessons.

My mom was, and still is, always around to listen if I wanted to talk. Her own mother never supported her emotionally, so in raising us, she always made herself available for long conversations, which back in the day consisted of mostly her lecturing at me. But in our adult relationship, she’s not afraid to talk about deeper topics and analyze complex decisions around career and relationships with me. I know many people who don’t really talk to their parents beyond surface-level topics, and I feel extremely lucky. Last week we talked about parenting for over two hours.

My mom was hellbent on the importance of education. She invested in our education, if not financially then personally. When she thought Chinese schools weren’t teaching me enough Chinese, she tutored me herself. If we did poorly on a quiz, she was willing to put in weekends with me or my sister to analyze what went wrong, read our textbooks with us, and learn together.

My dad was, and still is, a curious man and a playful spirit. When he’s up for it, he’s an incredible intellectual sparring partner, questioning my logic and challenging me with hypothetical scenarios to everything and anything. He’ll listen to me blab about interesting news, hobbies, observations, then offer his perspective on whatever subject without brushing it off. When he was off work, he’d play with us, teaching us chess, Chinese calligraphy, soldering… whatever we wanted to know. He was foundational to my own sense of curiosity, a core tenet of who I’ve become as a person.

By circumstance, we made the local library a second home. This may have just been a poor family’s way of getting daycare, but spending hours at the library after school surrounded me with the endless stories and high quality knowledge that shaped me. From books, I learned how to draw, read, do research, get lost in other worlds, and fulfill my curiosities.

My parents demonstrated what it meant to work hard. My dad juggled multiple jobs while my mom raised my sister and me while going through grad school and career changes. They were always improving themselves or supporting the family, rarely allowing themselves to have downtime. They modeled what it meant to hustle. We were taught to work equally hard. No excuses.

Summer 2005.

Summer 2024, in the same yard.

Things I’d do differently

As Asian parents, they didn’t exactly respect us as children. Children were meant to be seen, not heard. Because he was the “adult,” my dad would silence me for voicing my opinions (which were many times wrong but nevertheless valid). Coupled with his impatience, he would yell at me to shut up whenever I started raising my voice. They’d constantly repeat phrases like “get out of my house” and “I would’ve been happier if I’d raised a dog instead.” I’d feel completely worthless after some of their tirades, afraid but also rebellious. I’d have such low self-esteem that I’d fight back, but mainly to prove to myself that I’m better than my parents thought I was.

My dad had little patience and angered easily. He’d often tell me to hurry as I talked. He would have outbursts when he found out I wasn’t studying as planned, and in a fit of anger, throw everything off my desk or rip up whatever time-wasting activity I was doing instead in front of me (drawings, etc). I didn’t trust him to know what I was up to, and I’d hide everything I valued in fear and anticipation. My mom on the other hand would raise her voice at me, and when I talked back, she’d hit me. Not violence, but a good backhanded slap for shock factor. Stubborn me knew just what to say to inflict the most emotional pain, so naturally we fought a lot. This method of arguing would never lead anywhere good. As a parent, I don’t want to ever lose my temper at my own kids in a way that turns physical. Patience is one of the biggest virtues in which I know I have plenty of room for improvement.

They never failed to remind my sister and me of our flaws and shortcomings. The comparisons to other kids in their social circles, even fictional characters from movies, never ended. After my 10th birthday sleepover, my mom sat me down to analyze which of my friends were the most mature and admirable. Things like that made me ultra-competitive. I needed praise and validation, which my parents didn’t give out freely. Like many Asian American kids, I grew into an adult with crippling insecurity and a desperate need to please my parents with my life choices. They didn’t trust in my abilities to ever meet their expectations, and I didn’t trust myself to be enough. This has changed since, but required lots of self-therapy to fix.

My type-A mom is a serious woman, and lectured a lot, often projecting her own insecurities onto me. She instilled in me a deep-rooted fear of wasting time, which has spawned lots of anxiety and traumatizing guilt. In turn, I don’t know how to relax, which makes life hard to live. I don’t want my kids burning out from perfectionism and the need for external validation.

Conceptually, I agree that education is important, but as someone who grew up in the American public education system, I also know that a GPA or test score isn’t indicative of intelligence, resourcefulness, and true learning. I want my kids to actually learn, not to just get good grades. I don’t think my parents ever saw beyond that.

Perhaps this is a cultural thing, but my parents were not good communicators. Instead of setting clear expectations, they reprimanded me afterward for not meeting them. My mom wanted, and still wants, me to read her mind and anticipate what she’s thinking. Growing up in a guess culture “saving face” household made it hard for me to assimilate to ask culture elsewhere in America, and vice versa whenever I was home. Not sure if it was due to a lack of time or patience, but I’ve found that they never liked to explain things to me, especially “adult” concepts like how banking worked or complex family dynamics. So being the rebellious teen, I was always pushing their buttons, inquiring but getting nowhere.

Body image. Not saying my parents were vain (intelligence was definitely #1), but they commented on my weight often. Older generations of Chinese people claim they do this with love, but I’ve seen and experienced the harmful mental health side effects and the trauma it creates, especially in women. For example, my mom is aging, getting increasingly frail, and still tries to diet to maintain her figure. These comments truly stay with you your entire life.

My expanded family.

Things I admire about my in-laws

Simon’s dad is extremely patient. In almost ten years, I’ve never seen him get angry. Out in the world, he would strike up a conversation with anyone, and becomes friends with everyone. He’s reliable, dutiful, and punctual, traits that Simon inherited that will make him a great dad.

Simon’s mom loves being a mom, even with her grown children. She immediately took me in as one of her own when Simon and I first started dating, and she is always thinking about other people’s children. In her motherly way, she invites everyone to lavishly prepared holiday meals. She’ll host and cook for 3 separate Chinese New Year gatherings each year just so more people can be included. She and Simon’s dad are also both older siblings, so they’ll initiate gatherings to keep the family bonded. Simon’s close family environment is one in which I want our children to be born.

As opposed to mine, his parents are both overly communicative. They’ll always reach out. If my parents observe guess culture, Simon’s family is the prime example of ask culture. Plans for big dinners and outings are always made clear ahead of time. The lack of guessing just makes life easier to live.

They are very proactive in their friend circles, fostering a tight community through constant visits, phone calls, and generously thoughtful gifts. The amount of unannounced house visits they get on Chinese New Year from neighbors, friends, old clients, and friends of friends only begins to reciprocate what they’ve done for others. Having this community around means there is always someone to go to for help, whether it’s with home improvement, babysitting, or even tax advice.

Things I’d do differently

The constant fear and anxiety. Simon’s mom is often anxious, and has passed it onto her kids. Biking was too dangerous to learn. Swimming was unnecessary to master… Simon can just stay away from all water. Even passing through Oakland is risky. I on the other hand grew up playing outdoors, learning tricks on bikes, playing in pools, camping with my class. And I want my kids to do so as well without incessantly worrying.

Not having a private life outside of kids. Simon’s mom based her identity and her life around being a mom so once her kids grew up, she couldn’t stop. To this day she is still overly-involved in her grown children’s lives, calling daily and doing things for us we can 100% do ourselves.

Related to that point, a lack of independence projected onto their children. Simon’s parents insist on doing everything with and for their children, oftentimes guilt-tripping them for not spending “enough” time with them even though we see them weekly. And because he was raised in that co-dependent environment, Simon tends to rely on them (or nowadays, me) to make simple decisions.

Health, fitness, and nutrition. Because our grandparents’ generation had worked so hard to escape true poverty and manual labor in rural China, and our parents had worked just as hard to immigrate to this country and buy a house, it’s common for Asian families to spent most of their time cooped up at home. So respectively, Simon and I grew up at home with sedentary lifestyles. At the same time, an immigrant scarcity mindset paired with burgeoning white-collar means meant an overabundance of food at the dinner table, including processed American food. So as kids, we never really learned about nutrition either. We were told vegetables were good for us, but there is so much more to consider when it comes to macros, nutrition facts, and navigating the obesogenic American food landscape. This problem is much larger than our parents’ parenting preferences, but I want to give my kids the health education the American public fails to teach.

Evaluating my values

And that brings us into the here and now. At the start of Woj’s book, she asks us to reflect on our experiences in each of these values and how we plan to practice them in childrearing. As I read through the book, I added more detail to add color to each of these values, as a way for me to take notes and turn them into parenting advice for my future self.

TRUST — I want to trust my kids to make good on their word. I want to trust that they have the confidence to take calculated risks and keep themselves safe when engaging with the outside world. I want to trust them with adult responsibilities (e.g. feed themselves, shop, navigate directions, manage time) early on and feel empowered, even as kids. I want to trust that they will be good human beings, and remind them that perfection is never the goal. I want to trust myself in knowing I’ll be a more than capable parent who knows what’s best for my family.

RESPECT — I want to be patient with my kids and accept them for who they are, giving them the opportunity to lead and make mistakes along the way. I want them to think that their opinions and ideas can contribute, even in the smallest of ways, like dressing themselves or picking out what to eat. I need to support them but also hold them to standards. I won’t project my own dreams, insecurities, or ego onto them, and hopefully mold them into confidence individuals who listen to themselves.

INDEPENDENCE — I want to raise my kids with the amount of independence and responsibility my parents give me. I want them to own their own lives and take of business, whether it’s meals, cleaning, and homework as early as possible. I want my girl(s) to feel the same sense of ownership over their own decisions as boys do. I want to expose them to doing and overcoming hard things, to build their confidence as independent individuals. I plan to support their curiosity and develop their imaginations. And never overindulge or snowplow obstacles out of their way.

COLLABORATION — I want to be authoritative, but still have my kids to collaborate on as many family decisions as we can, so they feel like they’re contributing. I want to expose them to external groups so they can learn to work with others, whether through volunteering or team sports. I want to grow alongside my children, modeling what it means to be an imperfect person with a growth mindset.

KINDNESS — I want my home to be a kinder environment than the one I grew up in. I want to model gratitude and appreciation for the everyday, rather than be caught up in rewarding material successes. I want to teach my kids kindness towards others and just as importantly, towards themselves. I want them to develop a sense of purpose larger than themselves, and pursue a life of meaning beyond financial success.

This is me courageously, blindly, naively writing out a manifesto for parenthood, where everything sounds great in theory. But I’m sure the moment will come hard and fast, when I realize it’s tougher than it seems and I’m failing as a mother in between temper tantrums. But at least I know my values now. It’ll be fun to reflect upon years later.

Reflecting on my own upbringing before we bring up the next generation.